It is now clearer than ever that industrial livestock cannot be part of the sustainable food systems of the future. With industrial feedlots requiring huge quantities of feed crops, livestock systems occupy nearly 80% of global farmland, have a devastating impact on biodiversity, and generate 14-30% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

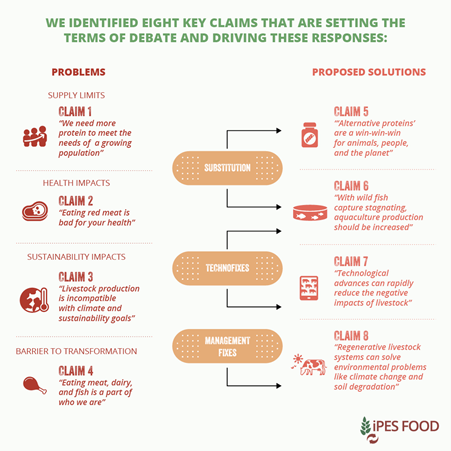

Few now question that reality – but there is less agreement on what to do about it. Indeed, farmers, consumers and policymakers alike are being assaulted by vocal and conflicting claims about the way forward.

Some are touting the potential of methane digesters, animal facial recognition technologies, and other techno-fixes for factory farms, with big meat firms like Cargill promoting “digital disruption” of meat production. Others are banking on turning livestock into a climate solution through rotational grazing, with giant manufacturers like General Mills promising to “advance regenerative agriculture on 1 million acres of farmland by 2030”. For the Director-General of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, and many others, scaling up aquaculture is the solution to our protein needs, in the face of stagnating wild fish capture.

Meanwhile, a growing number of voices are calling for a shift to plant-based substitutes, lab-grown meat, and insect-based protein products. According to Patrick Brown, the outspoken CEO of Impossible Foods, livestock is “the most destructive technology on earth” and ‘alternative proteins’ are “the last chance to save the planet”. Bill Gates, a big investor in the sector, has even declared that “all rich countries should move to 100% synthetic beef”.

The common thread that runs through these various ‘solutions’ is the need to keep delivering large quantities of ‘protein’ – whether from animals or plants. Noel White, an executive at meat giant Tyson Foods, has stated that “by 2050 global food systems will need to double protein production to meet the needs of almost 10 billion people”. Tyson has duly rebranded itself as The Protein Company, and Maple Leaf Foods has outlined its vision to be “the most sustainable protein company on earth”. In parallel, the food industry is marketing ever more ‘high-protein’ items to shoppers – even protein-enriched bottled water – and high-protein fad diets are growing. In media coverage and political debate, the vast challenges in our food production systems are regularly reduced to a single metric: how to get more protein for less CO2.

But there are big problems with this way of looking at food systems. In IPES-Food’s new report on The Politics of Protein, we took stock of the most vocal claims being made about meat and protein, finding that many of them rest on shaky foundations.

Firstly, the protein obsession is a legacy of now-debunked thinking. With ‘nutritionist’ approaches gaining traction, and meat and dairy industries seeking export opportunities, for decades development programs were dominated by protein-enriched therapeutic products. Protein became big business: at their peak, infant formulas for development aid accounted for 15% of US annual dried milk exports. These approaches had been largely debunked by the 1970s, and daily protein recommendations revised down. Today, the evidence clearly shows that there is no global protein shortage: protein is only one of many nutrients missing in the diets of those suffering from hunger and malnutrition, and insufficiency of these diets is primarily a result of poverty. But the idea of a ‘protein gap’ remains pervasive – and is being exploited by corporations to justify new protein-centric solutions.

Secondly, while they can theoretically reduce GHG emissions, it is unclear whether ‘alternative proteins’ or techno-fixes for industrial feedlots and fish farms will really deliver these gains (let alone address other sustainability challenges), in light of the way today’s food systems operate. Any solution that reinforces the factory farming model merely kicks the can down the road: it deepens the dependency on land and GHG-intensive feed production, and propagates the conditions (density, genetic uniformity) that allow diseases to emerge and spread. As for ‘alternative proteins’, while start-ups may have initiated the boom, the world’s biggest meat and dairy giants are now rolling out their own meat substitutes – making it hard to imagine a meaningful shift away from business-as-usual. Highly-processed products like the Impossible Burger and Beyond Burger source their ingredients from chemical-intensive (and therefore fossil fuel-intensive) monocultures that harm biodiversity, while lab meat relies on high-energy manufacturing processes and – as noted by the IPCC – can only deliver GHG savings if energy systems are decarbonized.

Thirdly, context is crucial, and tends to be ignored in blanket claims about livestock. In some parts of the world, raising animals helps to use limited land and resources efficiently, buffer against food shocks, and provide livelihoods where few options are available. Livestock plays a crucial economic role for approximately 60 % of rural households in developing countries, while fishing (often using small-scale, sustainable practices) is a primary source of livelihood for the 37% of the world’s population living in coastal communities. Access to fish is also crucial for more than 3 billion people – and can be undermined when fish species that could be consumed locally are shipped across the world as feed for salmon or trout farms.

Despite all the false solutions and misleading claims, what we do need to do remains surprisingly clear. We do need to change our diets – but not by replacing one industrial product with another. We need diversified agroecological production systems; regional food strategies that reintegrate crops and livestock, and use land and resources efficiently; food environments in which the healthy and sustainable option is the easiest; less processed foods, and more diverse diets based on a range of nutrient-rich foods, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and pulses – also including meat, dairy, eggs and/or fish in some regional contexts. In other words, we need a sustainable food system transition, not merely a protein transition. These solutions do not have billionaires and bombastic claims behind them – but they are working on the ground, and urgently need more support.

For wealthy countries where meat and dairy are currently consumed to excess, the transition towards “less and better” meat – long advocated by scientists and civil society groups – is clearly the right direction. Ultimately, each country and each region will have to work out precisely what that looks like, as they chart their own course to sustainable food systems and animal production systems. But one thing is clear: we must stop buying into the protein hype, and start asking the right questions.

By Nick Jacobs, Director of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food)

More information:

- Read the full report by IPES-Food: The Politics of Protein

- Learn more about IPES-Food - the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems